Apostolic Succession

Apostolic succession is defined as an unbroken chain of ordinations back to the Apostles which is God’s method for preserving orthodoxy in the worldwide Church. There is a sacramental process (laying on of hands, blessed by the Holy Spirit) which transfers a gifting and authority from God to the apostles and each successive generation of bishop. Is this taught by Scripture? Was it the model for the early church?

In the world’s most hostile environments to Christianity—Islamic states and underground China—the only movements responsible for church growth are decentralized, confessionally driven networks, not sacramentally bound episcopal hierarchies. This strongly suggests that Reformed-style ecclesial structures could more closely resemble the early Church’s functional reality.

God inspired Scripture, and yes, He providentially guided the canon’s reception. Does He also inspire each successive generation of bishops in that same way? Fully and inerrantly? Due to heretics popping up continually throughout church history—men who had hands laid on them by prior bishops—the answer is clearly no. And notice that God repeatedly works through faithful remnants and prophetic voices outside His institutions while official structures rot. That isn’t God “abandoning the earth.” It’s God refusing to be domesticated by any one single human recognized pedigree. The Church comes from the womb of God the Holy Spirit and is curated and lead by Him.

There is a false dichotomy in claiming that God either remains with certain church institutions and inspires them to the same full extent as He did Scripture, or He abandons the earth. During Christ’s earthly ministry, God was working outside the Levitical priesthood and almost entirely through an underground movement—no priestly garb, no official name, no headquarters. Just God and the faithful.

Reformed networks tend to disagree with the notion of a supernatural chain of custody being required by God. They state that later medieval developments in Catholic and even Orthodox views on clergy were not taught by Scripture nor practiced by the early church. An apostolic church is a group of born again believers who teach, practice and adhere to the truth taught by the apostles as preserved in Scripture, not oral tradition.

God alone is to be looked to—without any man, office, or institution standing in the way. The claim that the Church cannot exist apart from an unbroken, tactile chain of apostolic succession is historically implausible, they argue, especially in light of the Church’s intense persecution and rapid underground expansion. Faithfulness to apostolic doctrine, not proximity to apostolic hands, is what the record actually demonstrates.

By AD 150, Christianity had spread from Judea to Gaul, North Africa, Mesopotamia, and India. Communication was slow, persecution constant, and episcopal structures uneven or embryonic. It is historically implausible that every new congregation waited for a verified, hands-on apostolic chain before existing as a “real” church.

Traditions of churches in Edessa, Persia, and India arose extremely early. Churches existed where direct apostolic verification was impossible. These communities were recognized as churches based on confession and teaching, not paperwork. For roughly 250 years, Christians met in homes, catacombs, and hidden assemblies. Many leaders were martyred quickly (Ignatius, Polycarp, Cyprian). Leadership continuity often meant local recognition of faithful teachers, not formalized succession ceremonies. Survival depended on doctrine and Scripture, not institutional continuity.

Lineages and Pedigree

High priests, Levites, and Pharisees boasted in genetic and priestly lineage. Christ largely bypassed them—working instead among commoners, outsiders, and even the mixed-race, heretical Samaritans. He told the Samaritan woman that the Father is now worshiped in Spirit and in truth—not at a sacred site, and not before a bodily priest validated by the “correct” succession (John 4:23–24).

When the Pharisees came to John the Baptist, he shattered their confidence in Abrahamic genetics and called them spiritually dead. What God demands is repentance, not pedigree. Obedience, not ritual.

“To obey is better than sacrifice.” – 1 Samuel 15:22

Jesus drove the point home in the parable of the Good Samaritan—exposing the Jerusalem priesthood as spiritually bankrupt while making an ordinary Samaritan the true neighbor.

Laying Of Hands

The laying on of hands is clearly a normative practice in the New Testament. It is a biblical act of recognition, blessing, and commissioning, and for that reason all branches of Christendom practice it.

Of the eight major commissions or appointments recorded in the New Testament, the laying on of hands is explicitly mentioned in four:

- Seven deacons appointed ✅

- Paul and Barnabas commissioned ✅

- Timothy commissioned by elders ✅

- Timothy commissioned by Paul ✅

It is not described in the others:

- Elders appointed in Galatia ❌

- Matthias replaces Judas ❌

- Titus appoints elders in Crete ❌

- Ephesian elders addressed ❌

The presence or absence of description, however, is not the central issue. The real question is where authority comes from.

One may fully affirm that the laying on of hands is commanded by God and that it conveys real, supernatural blessing—without believing that its efficacy depends on an unbroken human chain traced to a specific source. God does not operate with a merely horizontal genealogy of hands, but with a vertical, bird’s-eye view of obedience to His truth.

Authority is granted by the Spirit to those who hold fast to apostolic doctrine and walk in obedience. The New Testament never teaches that truth is secured by pedigree, but by fidelity.

Powerful Greek evangelist Apollos was not chosen by apostolic authorities yet the Scriptures condone his ministry. In the first two hundred years of the New Testament church powerful orators Justin Martyr, Tertullian and Clement of Alexandria were pillars of the early church and were neither priests or bishops.

Second- and fourth-century historians Irenaeus and Eusebius preserve detailed episcopal lists for major sees like Rome, Antioch, and Jerusalem, with fragmentary records elsewhere. This shows that the early Church cared about historical continuity—but it does not prove that continuity functioned as a supernatural guarantor of doctrine.

How Many Offices Are There?

In the New Testament, bishops (episkopoi) and elders (presbyteroi) are not separate ranks but overlapping terms—often referring to the same office and even the same men (Acts 20:17, 28; Titus 1:5–7). Scripture knows no hierarchical distinction between them. The later separation into distinct offices did not arise from apostolic mandate but from administrative consolidation as the Church responded to growth, persecution, and heretical fragmentation. In the New Testament, local churches are consistently led by a plurality of elders/overseers, never by a solitary ruling bishop.

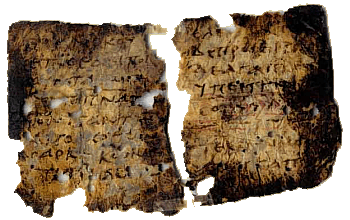

Latin fragment of the Didache (Doctrina Apostolorum) – 4th–5th century

What is likely our earliest Christian writing outside the New Testament is a collection of church protocols long believed to reflect the teaching of the Twelve Apostles. Known as the Didache (“The Teaching”), it contains sixteen short chapters covering five basic areas:

- Ethical instruction for converts

- Liturgical and sacramental practice

- Church governance and leadership

- Church discipline

- End-times expectation

In Didache chapter 11, three ministries are described as non-local and mobile across the universal Church: apostles, prophets, and teachers. But when the text turns to local leadership, chapter 15 is explicit:

“Appoint therefore for yourselves bishops and deacons worthy of the Lord, men meek, and not lovers of money, and truthful and approved; for they also minister to you the ministry of the prophets and teachers.”

- Didache, ch. 15:1-2

Hippolytus of Rome’s 215 AD Apostolic Traditions backs this up:

“Let a bishop be ordained after he has been chosen by all the people. When he has been named and approved, let the people assemble on the Lord’s Day, with the presbytery and the bishops who are present.

Let all give their consent. Let the bishops lay hands upon him, and let the presbytery stand by in silence.”

- Apostolic Tradition, 2.1-3

Here again, congregational election precedes ordination. The laying on of hands follows recognition—it does not create authority in a vacuum. This cuts to the heart of the issue. It appears God was not working from bishop to bishop but congregation by congregation. Leaders emerged from among the people (as would an athlete or businessman) and were recognized as chosen by God and their willingness to obey Him. Bottom up. Not top down.

Was the Holy Spirit involved? Of course. Was this involvement in the form of only giving the leaders supernatural insight as to who was next? No. Congregations were noticing who was next and existing leaders would “double check” for moral character and proper doctrine. As history has taught us, this is no guarantee that congregations or leaders have a 100%, inerrant track record. But a robust and hefty core of doctrinally sound believers has existed since Christ’s earthly ministry.

Church Fathers on Ordination

Clement of Rome, writing 1 Clement around AD 96, presupposes a plurality of bishops and elders within each church. As in Acts, the terms bishop and elder are at times interchangeable, referring to the same men, with no internal hierarchy described among leaders in a city. Clement affirms that the first generation of bishops and elders were appointed by the Apostles, and that provision was made for succession:

“They appointed those already mentioned, and afterward gave instructions, that when these should fall asleep, other approved men should succeed to their ministry.”

- 1 Clement 44.2

But Clement never explains who approves the next generation of approved men. When read alongside the Didache and the Apostolic Tradition, the pattern that emerges is not bishop-only appointment, but local election with communal and clerical discernment—a congregation and its leaders prayerfully recognizing qualified men.

This same emphasis appears in The Shepherd of Hermas, written in Rome at the close of the first century:

“The presbyters who preside over the Church are those who are faithful and modest, and who have never coveted the first seat.”

- Vision 2.4.2-3

“Those who preside are approved if they walk in righteousness.”

- Similitude 9.27.2

Again, leadership is plural, recognition is communal, and moral qualification is decisive. Hermas goes further: in Mandate 11.1–2, a corrupt authority is said to be inferior to a righteous layman who humbly practices truth.

By the mid-third century, Cyprian of Carthage (Epistle 67.3–4, c. AD 250) still describes episcopal ordination as involving:

- election or rejection by the people,

- testimony and consent of the clergy, and

- ordination by bishops—

with moral and doctrinal fidelity serving as grounds for legitimacy or disqualification.

In his epistle to the Philippians (~110-130s AD) Polycarp mentions a plurality of elders as proper leadership. Never a singular bishop. In fact, he never once mentions bishops. This epistle only discusses moral rectitude as the foremost qualification for leaders. He even mentions an elder that was deposed due to unrighteousness. The office was not permanent. No protocol is described for succession in leadership.

from left to right: Clement of Rome, Shepherd of Hermas, Polycarp and Ignatius of Antioch

Writing at the beginning of the second century, Ignatius of Antioch is the first to clearly articulate a model of singular episcopal (bishops) authority over a local congregation and its presbyters (elders). Across his seven letters, Ignatius never explains how a bishop is chosen, but he consistently assigns the bishop primacy. Elders are portrayed as subordinate (Eph. 4.1–2), and the bishop is said to act “by the mind of Jesus Christ” (Eph. 3.2). Believers are warned not to resist the bishop (Eph. 5.3) and are exhorted to regard bishops, presbyters, and deacons as images of Christ, the Father, and the Apostles (Eph. 6.2; Mag. 6.1; Tral. 2.1; 3.1).

Ignatius goes further in his Letter to the Smyrnaeans:

“Let no man do anything connected with the Church without the bishop…

…Let that be deemed a proper Eucharist, which is administered either by the bishop, or by one to whom he has entrusted it…

…It is not lawful without the bishop either to baptize or to celebrate a love-feast.”

- letter to the Smyrneans 8.1-2

Crucially, Ignatius writes in direct response to Docetist and early Gnostic heresies, which denied Christ’s flesh and therefore rejected the Eucharist itself. In Smyrna, doctrinal confusion threatened to fracture the Church. Ignatius responds by centralizing authority around a single bishop to clearly distinguish which assemblies and home groups were adhering to biblical doctrine and which were heretical assemblies. It was a matter of doctrine not recognizing a new sacramental mandate from God.

Read in context, Ignatius’ move is best understood not as a timeless apostolic blueprint, but as a strategic consolidation of authority under doctrinal threat. This is later confirmed by Jerome, who states that bishops and elders were originally the same office, and that the distinction arose by custom to prevent schism, not by apostolic command:

“Before factions arose… the churches were governed by the common council of presbyters… afterward one was set over the rest to remove the causes of schism.”

- Jerome, Commentary on Titus 1:5 (c. AD 396)

In other words, the mono-episcopate was a practical response to crisis, not a mandate handed down from the apostles.

Early Fathers appealed to succession because, at that time, apostolic truth and those publicly entrusted with guarding it occupied the same visible lineage—making succession evidentiary of doctrine rather than an independent authority.

First Council of Nicaea

The 1st Council of Nicaea (AD 325) addressed the ordination of bishops—not their election—in Canon 4, stating:

“It is by all means proper that a bishop should be appointed by all the bishops in the province; but should this be difficult… three at least should meet together… and then the ordination should take place. But in every province the confirmation of what is done should be left to the metropolitan.”

- Nicaea I, Canon 4

This canon explicitly regulates who performs the laying on of hands (bishops, under a metropolitan) but does not forbid, mention, or negate prior patterns of congregational nomination or consent. That omission is significant, since post-Nicene fathers continue to speak openly of popular involvement. Athanasius in the 350s AD condemned bishops imposed “without the consent of the people” (Apology Against the Arians 6), Ambrose of Milan was chosen bishop by public acclamation—“Ambrose, bishop!”—by the gathered people in 374 AD (Paulinus, Life of Ambrose 7–8), and Hilary of Poitiers (~359 AD) rebukes bishops “forced upon churches against their will” (Against Constantius 4). Thus, Nicaea standardized episcopal ordination mechanics without explicitly abolishing the long-standing role of congregational involvement in identifying the candidate.

At Nicaea, all heretical Arian bishops had been ordained from the same growing tree branches of apostolic succession as the rest of the bishops. Yet this was never addressed as being of any concern or benefit. In fact, after their defeat at the council, the emperor, Constantine, launched his ‘Edict against Arius’ deposing and removing sacramental powers from bishops who refused to sign the Nicene Creed. Doctrinal fidelity was the beginning and end of the discussion.

With the regional council of Laodicea in 363-4 AD and its canon 13, the Church for the first time explicitly begins restricting popular election. Marking the decisive conciliar break from earlier models in which elders and bishops were chosen with direct congregational involvement. Historical evidence from the late 4th and 5th centuries shows that popular consent and congregational involvement in ordinations persisted in parts of both the Eastern and Western churches, requiring repeated attempts to restrain it. Yet, from this point forward, such participation did begin to disappear as normative.

Succession lists were used polemically to show teaching continuity, not sacramental magic. The argument was: “Our bishops teach what the apostles taught” — not “Their hands contain ontological authority.”Of course we should expect—and do see—a historical line of men who remained faithful to apostolic teaching. But this reality props up no single later tradition—Orthodox, Catholic, or Reformed. It simply bears witness to biblical fidelity and its preservation in history.

Scripture As Highest Authority

In the great council battles of the fourth century, orthodoxy was not defended by appeals to episcopal lineage but by direct appeal to Holy Scripture. The Arian bishops who opposed Nicaea possessed the same external apostolic succession as their orthodox counterparts, yet this fact carried no argumentative weight at the councils. Instead, bishops like Athanasius contended relentlessly from the text of Scripture itself—“of one essence with the Father” defending his thesis by biblical exegesis, not by pedigree. Creeds were forged as scriptural summaries, heretics were refuted by biblical contradiction, and councils judged doctrine by conformity to the apostolic writings, not by an unbroken chain of hands. Succession without scriptural fidelity proved meaningless; Scripture, not lineage, functioned as the supreme court of appeal.

The early Church did not teach a “both lineage and doctrine” rule of authority, because when the two came into conflict, lineage was set aside and doctrine alone prevailed. Appeals to succession in early writers served as historical evidence of where apostolic teaching had been publicly maintained, not as identifying a single family tree and excluding anyone physically outside of it. It perplexed the disciples to see unknown men casting out demons in Christ’s name:

“Teacher, we saw someone casting out demons in your name, and we tried to stop him, because he was not following us.” – Mark 9:38

But Christ saw men with fidelity to His Name and message, so He blessed them:

‘Do not stop him… … For the one who is not against us is for us.” – Mark 9:39-40

IN CONCLUSION

In the Old Testament, entire priestly lineages were rejected despite impeccable succession (the house of Eli, 1 Sam 2:27–36), while prophets with no institutional pedigree—Amos explicitly denying any prophetic lineage (Amos 7:14–15)—were raised up by God to speak with full authority. John the Baptist ministered outside the Temple system, and Christ Himself confronted a fully intact priestly succession while condemning its leaders as “blind guides.”

Paul rebuked fellow apostles when they deviated from the gospel (Gal 2:11–14), and warned that even angelic or apostolic authority must be rejected if it contradicted the received message (Gal 1:8–9). Most decisively, the Bereans did not authenticate Paul by appealing to his apostolic credentials or to unwritten Mosaic traditions, but by examining the written Scriptures daily to test whether his teaching was true—and they were explicitly applauded for doing so (Acts 17:11).

The early Church never taught that God requires both tactile succession and sound doctrine; it taught that succession has value only insofar as it testifies to sound doctrine.

To quote early fathers who spoke of “us vs. them” as though they were not speaking of heretics is to misunderstand history. They did not mean that — no matter how apostolic the teaching of the “other” group was — if it wasn’t someone they already knew, they were outside the church. This issue had already been dealt with when the disciples of Jesus noticed a different group performing exorcisms (successfully) in Christ’s Name. The disciples were upset and even stopped this group. When they brought this to Christ’s attention He said plainly:

“‘Do not stop him, for the one who is not against you is for you.’”

– Luke 9:50

If you have received and are teaching apostolic doctrine (as detailed in Scripture) you are part of the one, correct (orthodox), worldwide (catholic) apostolic Church.

Scripture and the earliest Fathers recognize no rank distinction between bishops and elders, and because congregational recognition was integral to ordination, there is no principled argument against Luther as a validly ordained presbyter—or against the continuity of bishops and elders arising from his branch and the laity who participated in their promotion.

Where Christianity faces conditions closest to the early Church—persecution, illegality, and dispersion—the forms that actually grow are decentralized, elder-led, and doctrinally cohesive, not bishop-dependent sacramental systems.

Wherever God’s truth is faithfully proclaimed, there the Church truly exists.

And the Spirit promised to do just that.