Intercession of the Departed Saints and Martyrs

Catholic and Orthodox Christians ask the departed Christians — who have died here on earth but are very much alive on the Other Side — to intercede for them. After all, a saint that is more directly in the presence of God and finds themselves purified of all sin will have a powerful prayer, will they not?

Let us look at the early church to see when this practice first arose and what the Church Fathers had to say about it.

The New Testament Instructions on Prayer

The disciples approached Christ and asked Him, “Lord, teach us how to pray.” Christ’s response — because of its balance of worship, petition, confession and dependence on God — is widely regarded as the clearest, most authoritative prayer formula taught in the Scriptures.

“Our Father, who art in Heaven…”

Matthew 6:5-13 and Luke 11:1-4 recount this formula and show Christ modelling prayer directly to the Father. In other gospel passages Christ asks us to pray to “the Father in My Name…” (John 16:23-24). Paul calls Christ the only “one mediator between God and men,” (1 Tim. 2:5), and he also clarifies the role of the Holy Spirit as an intercessor and the power source of our prayers (Rom. 8:26-27, Eph. 6:18).

The pattern is clear. The Holy Spirit powers, formulates and aims our prayers towards Christ who then purifies and authorizes them so they are fit to be received by the Father.

Revelation 5:8 shows the cherubim and elders holding golden bowls of incense “which are the prayers of the saints.” This occurs in the very Throne Room of Heaven with both the Father and the Son present. Human and powerful non-human creatures are involved in our prayers reaching the Father through Christ as brought by the Holy Spirit. God the Father does not require His creatures’ participation but He involves them nonetheless.

Although the earliest Church Fathers (i.e.: the Apostolic Fathers) taught that the departed believers actively pray — intercede — for earthly believers, please note that this scene from Revelation 5:8 does not show the elders or cherubim bringing their own prayers to the Throne but bringing ours. Conduits of our prayers are the only activity being described here.

Hebrews 12:1 states that earthly believers are “surrounded by such a great cloud of witnesses.” Orthodox and Catholic believers claim this means we are being watched, prayed for and therefore able to interact with our departed brothers and sisters in Christ. However, all of the Apostolic Fathers who commented on this passage — including later Fathers such as Clement of Alexandria — interpret Hebrews 12:1 as teaching that we are to be inspired by the lives of the believers in the “Hall of Faith” described in the previous chapter of Hebrews. Not that they watch us nor are able to hear us.

Nowhere in the Old Testament, the Deuterocanon (Apocrypha) or the New Testament are we shown directly that we can entreat the departed with prayer requests. When Saul reaches Samuel he has to do so through the witch of Endor, in violation of Deuteronomy 18:10-12’s warnings against sorcery and witchcraft.

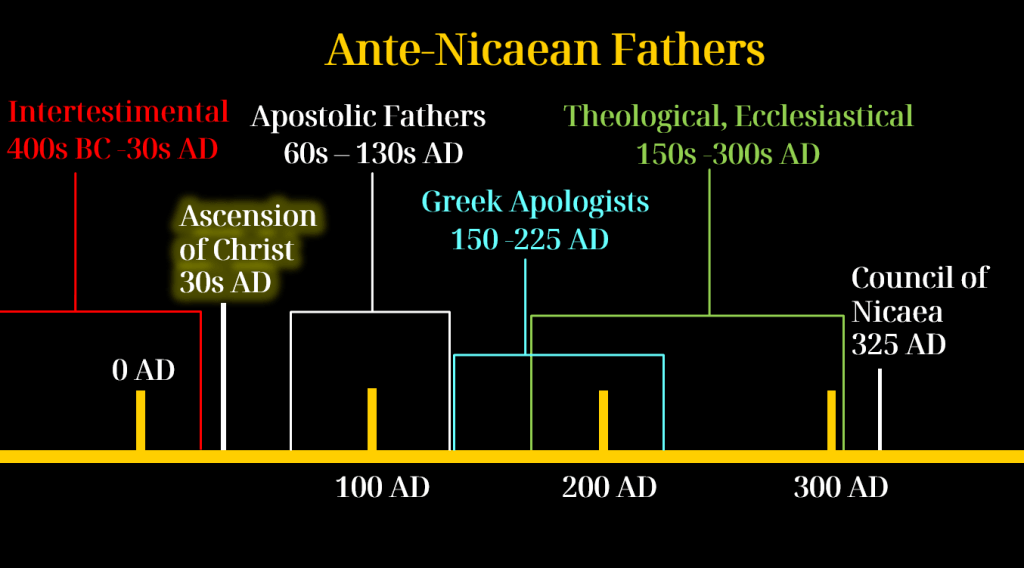

The Ante-Nicene Fathers

The period between the Ascension of our Lord and the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD is known as the pre or ante Nicene period. The church’s theologians and leaders during this era are known as the Ante-Nicene or Nicaean Fathers. Sub-categories such as Apostolic Fathers (the direct students of the Apostles and their students), Greek Apologists (e.g.: Justin Martyr) and Ecclesiastical Fathers are based on their chronological appearance and their main written contributions on faith and doctrine.

Apostolic Fathers

Nowhere in the first century after Christ’s Ascension do we see any student of the Apostles present instructions on prayer other than a mirror of the New Testament’s formula. Everything is directly prayed to God through Christ. There are no exceptions. Neither Clement of Rome, Ignatius of Antioch or Polycarp break this pattern. Prayers such as the following by Ignatius are the normative structure:

“Let us at all times give thanks to Christ Jesus, and to His Father, who has given us understanding, wisdom…”

Orthodox scholars such as Metropolitan Kallistos Ware and Catholic scholars such as Friar John A. Hardon, S.J. admit that the omission about invoking the departed is due to the absence of this practice during the first two centuries of Christendom.

Greek Apologists

Because they were presenting and defending Christendom to a Greco-Roman pagan world, these Church Fathers differentiated Christian practice from the paganism saturating Rome’s empire.

Justin Martyr, Theophilus of Alexandria, Athenagoras of Athens and all other Fathers from this period criticized the Greco-Roman pagan practice of invoking the departed spirits and warned against it.

“We do not pray to any originated thing, nor to angels, nor to archangels, nor to any being other than God, but only to the Maker and Father of all, to whom alone it is right to address prayer.”

- Clement of Alexandria, Stromata Book VII circa 202-205 AD

This distinction by Clement is a clear example that the Greek Apologists were continuing the straight line from the tradition of the Apostolic Fathers and the New Testament in reserving prayer as an act solely directed to God.

Some Orthodox and Catholic believers claim that this was an attempt to differentiate the Christian practice of invoking departed saints from the illicit pagan rituals for the dead. Yet if the Fathers were simply contrasting pagan parallels to Christian doctrine they would have clearly done so. Like when Justin Martyr used the Greco-Roman myth of virgin-born Perseus to teach on the true virgin birth of Christ. Or Origen’s use of Hercules’ post-death ascension to god-hood as a pagan pseudo-resurrection story. Church fathers used any pagan beliefs that paralleled Christian truths to point to Christ as the true manifestation of their archetypes. But this is not the case with communication with the departed. They unanimously distance Christianity from such practices as they did when warning against astrology and fortune telling.

Another often cited counter is that the fathers were only warning against worshipping creatures other than God. Praying to pagan idols was a worship problem, not an invocation problem. But the word for prayer in the New Testament is the same one used in the patristic warnings:

| προσεύχομαι |

| pro-SYOO-kho-my |

If they were concerned with worship, they would have used the word for worship. Which is the same one used in the New Testament warnings to not worship anything other than God:

| λατρεύω |

| la-TREH-oo-oh |

“Well, invocation of the saints is not prayer. So the patristic warnings were never against invoking departed saints.”

Invocation is not a separate category than prayer, it is a subset. One must address a being from the Other World before they can invoke them for a request. But even if we take this line of reasoning, Augustine explicitly used the word for invocation when he warns agaisnt it:

| ἐπικαλέω / ἐπικαλοῦμαι |

| eh-pee-ka-LEH-oh / eh-pee-ka-LOO-my |

Church Fathers in the Greek Father era who addressed prayer to created beings unanimously forbade the practice. Without exception. They kept the straight line of Scripture going. To impose a retroactive green light on invocation just because it later became normalized is to reinterpret clear prohibitions through later categories.

Ecclesiastical,Theological and Anti-Gnostic Fathers

As the late third century unfolded, we begin to see evidence that believers practiced invocation. Aside from the Garden Tomb of Christ, the oldest and most famous burial site in Christendom is that of Peter the Apostle’s. Dating to 64-67 AD it is home to the most often cited invocation inscription:

“PETRE, ROGA.”

“Peter, ask on our behalf.”

Although the tomb of Peter is from the first century, Margherita Guarducci — one of the Vatican’s chief archaeologists — dates(1) this inscription to somewhere between 270-319 AD because the lettering style is of the early fourth century and the inscription’s location is not at the original grave but on an adjacent red plaster wall added in late third century.

Priscilla, wife of a Roman Senator, was buried around 180-200 AD. The original nucleus of this family site was later expanded into a catacomb network in the mid third century. It is in these later expanded regions that we see the following inscription:

“ORATE PRO NOBIS.”

“Pray for us.”

Due to the lettering and location of the tiles they are inscribed on, archaeological scholarship(2) dates this after 313 AD.

San Sebastiano was a converted Roman soldier who was martyred under Diocletian’s persecution between 288-300 AD. His original burial place (i.e.: catacomb) in Rome only bears standard inscriptions wishing him peace. After Constantine legalized Christianity with the 313 AD Edict of Milan, famous burial sites such as San Sebastino’s were expanded in size and had new epigraphs carved into their new walls. These newer inscriptions show a clear practice of invoking departed saints.

PETRE ET PAULE MEMORES ESTOTE “Peter and Paul, be mindful of us”

“PETRE ET PAULE, PETITE PRO VICTORE.”

“Peter and Paul, pray for Victor.”

Both of these appear in the court in the catacombs of San Sebastiano. Catholic scholarship(3) sites the type of lettering used and the location of the inscriptions to determine they were made between 320 and 360 AD.

Church Fathers of the late ante-nicene period unanimously continued the explicit warning against directing prayer anywhere but directly to God:

“It is not our duty to pray to angels, nor to archangels, nor to any being created, but only to God, the Father of all, through our Saviour who is the High Priest.”

- Origen “On Prayer, Book IX v. 1” circa 233 AD

“One must pray to the one God the Father, through the Son and in the Holy Spirit, and pray to God alone, not to angels or creatures.”

- Novation “On The Trinity, Ch. 6 v. 2” circa 240s AD

Hippolytus of Rome, author of the Apostolic Traditions (~215 AD) and others such as Commodianus and Arnobius of Sicca, condemned contacting the departed, calling it sorcery.

In the early fourth century, Lactantius writes:

“Therefore, let us hold firmly the principle that it is God alone who hears and provides for what is foreseen and prayed for.”

- Lactantius, “Divine Institutes, Ch. 2 v. 14”

Again, the straight line of doctrine for prayer being to God alone continues all the way through to the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD.

Post Nicene Period

After Constantine’s Edict of Milan in 313 AD, the Church begins to adopt the practice of building shrines for the beloved martyrs of Christendom. Around 370 AD, at a dedication to the shrine of Christian martyr St. Julitta, Basil of Caesarea stated:

“At the tombs of the martyrs the whole city gathers together;

we pray, and the martyrs intercede.

It is the day of the martyrs’ feast—

heaven and earth are joined,

men converse with angels.”

“Julitta is an ever-wakeful helper for those who call upon her.”

- Basil of Caesarea, “Homily on St. Julitta the Martyr” circa 370 AD

This is the first known proclamation by a Church Father in favour of invocation. Yet, instead of a wholesale acceptance of this new practice, a war broke out among the ranks of the Fathers in this post-nicene period. To Basil’s side flocked notable allies such as Gregory Nazianzen, Gregory of Nyssa and Cyril of Jerusalem. And forming an opposition were heavy weights such as Aerius of Sebaste, Vigilantius of Calagurris, Eusebius and Augustine.

Eusebius, bishop of Caesarea, is known as the “Father of Church History” because he compiled the earliest and most comprehensive history of the first 300 years of Christendom. Although he wrote his doctrine of prayer before Basil’s homily, he was clearly writing to preserve the apostolic tradition in the face of the growing practice of martyr shrines and relics occurring in his time. From 312 to 335 AD he wrote multiple directions regarding prayer. Proclamations that oppose invocation include:

“We do not offer prayers to men, nor to angels, nor to the sun, nor to the moon, nor to the elements, nor to those who are called gods; but only to God who is over all do we send up prayers and acts of worship — to Him who also sent our Savior Jesus Christ, the divine Word, to mankind.”

- Eusebius, “Demonstratio Evangelica Book 3 ch.1 v.6” circa 310s AD

“We do not make gods of godly men, but we honor them with the remembrance of their piety.”

- Eusebius, “Demonstratio Evangelica Book 3 ch.6 v.30” circa 310s AD

The regional council of Elvira, Spain in 305 AD ruled against ceremonies focused on martyrs’ at their burial places:

“Candles shall not be burned in a cemetery during day, for the spirits of the saints are not to be disturbed. Those who do not observe this are excluded from the communion of the church.”

- Synod of Elvira, Canon 34

Often, Augustine of Hippo is cited as being in favour of invocation because he believed the martyrs and departed saints prayed for us and that we could pray for our departed family members. Yet, when I searched his writings on prayer, I only found strict warnings against invocation.

“Not the martyrs, but the God of the martyrs, is to be invoked.”

- Augustine, “Psalm 32, Sermon 2.29-30” circa 410 AD

“The Lord does not say, ‘You shall pray to me through the martyrs,’ but, ‘Whatever you shall ask the Father in my name, He will give you.’”

- Augustine, “Tractates on the Gospel of John, 21.1” circa 407 AD

Despite this controversial period, by the end of the 5th century, most churches in both the east and western Roman empire included invocation in their sermons and liturgical formulas. The regional council of Carthage, Africa in 419 AD is sometimes cited as being pro-invocation yet it merely addressed prayers for martyrs being allowed in the liturgies but never mentions making prayer requests to these departed saints. Yet, as time went on, there is less and less controversy recorded regarding invocation and the practice became ubiquitous throughout Christendom.

By the end of the 8th century, invocation had become so completely a part of Christian prayer life that the ecumenical (i.e.: universal) Second Council of Nicaea made it canon:

Thus, according to the teaching of our holy Fathers, we rightly and truly honor and invoke the saints, asking their intercession, for they offer prayers to God on our behalf.

Icon depicting the second Council of Nicaea (787). Paris. France

In the hundred and fifty years before the Reformation officially kicked off in 1517 AD, men within the Roman Catholic system — such as catholic priests John Wyclif (1328-1384 AD) and Jan Hus (1372-1415 AD) — began to revisit and question the theological legitimacy of invocation. Catholic monk Martin Luther followed in the growing catholic dissent against certain matters of dogma. This disagreement combined with many other grievances eventually leading to the catholic schism that birthed the Reformed tradition in the West.

IN CONCLUSION

The Ante-Nicene Church displays a consistent and unanimous pattern: prayer is directed to God alone, the departed are honored but not addressed, and no Christian source before the late fourth century approves or models invocation of saints.

After Basil’s proclamation, the Fathers fought for nearly a century over invocation. Then, nearly a half millennia after Christ, it began its climb to normative practice. It wasn’t God giving His bishops continued illumination on the inner workings of Heaven it was development without apostolic warrant. Which is precisely how error enters historically.

Considering the explicit directives to pray solely to the Father through Christ given to us by our Lord Himself and the continued instructions to do so by all of the Ante-Nicene and many Post-Nicene Fathers, it appears inarguable that directing something as sacred as our prayers to any other than our Creator is against God’s Will.

Even God-ordained systems like the Levitical Priesthood and Sacrificial System were corrupted over time. Should we be surprised that yet another God-Willed earthbound institution can also be vulnerable?

Although I will say that I have very few points of disagreement with the original Seven Ecumenical Councils, I do not view these as equivalent to Scripture. And herein is the main difference between the Orthodox and Catholic view of Christendom’s history and that of non-denominational or Reformed Christians. To Catholics and Orthodox believers, the Holy Spirit inspired the authoring of Scripture and later its official Canonization. Which is a belief shared by myself and any Reformed theologian. Yet the Catholic and Orthodox theologians extend the ministry of the Holy Spirit to beyond this and all the way to, at least, the first seven Ecumenical Councils. This is known as the Holy Tradition.

My reflex against extra-biblical traditions being viewed as on par with Scripture comes from warnings from ecclesiastical history. It was the supposed oral traditions of Moses (not included in the Old Testament) that were embraced by the Pharisees and lead to a myriad of theological errors by the time of Christ. Throughout the Old Testament the prophets sent by God to reform Israel emphasized the written word of God as the bedrock of His teachings.

When the Scriptures and the nearly 4 centuries that followed Christ give unqualified prohibition on a matter of faith and doctrine, I will make this my orthodoxy.

___________________________________________

footnotes:

1. Margherita Guarducci, I graffiti sotto la confessione di San Pietro in Vaticano (Vatican City: Pontificia Accademia Romana di Archeologia, 1958)

2. Antonio Ferrua, Le iscrizioni dei cimiteri cristiani antichi di Roma (1953)

3. De Rossi, Roma Sotterranea, vol. II [1867], pp. 211–220; Ferrua, Le iscrizioni dei cimiteri cristiani antichi di Roma, 1953.

___________________________________________