On the Veneration of Icons

In 787 AD, the Second Council of Nicaea dogmatically defined the act of the veneration of icons. This was the main reason for the seventh, and last universal council before the Great Schism of 1054 AD.

“What in the world does it mean to ‘venerate icons?”

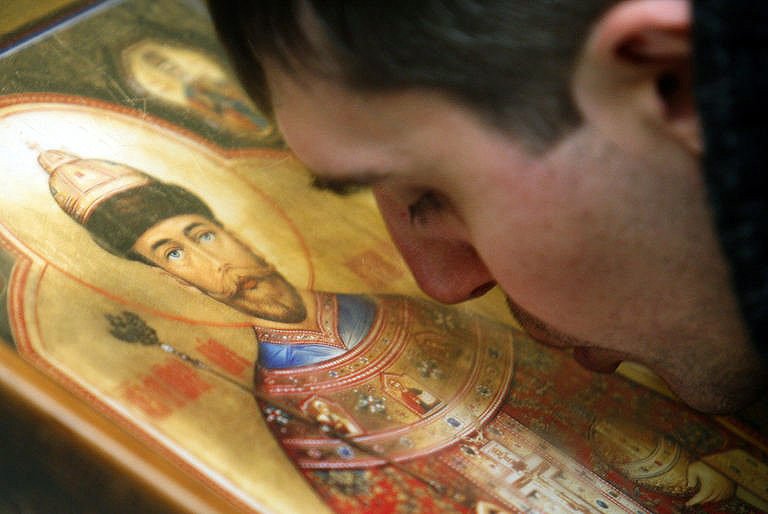

Icons are images of Christ, Mary the Holy Mother, John the Baptist and other saints of Christendom placed in a church or home. Veneration of these images encompass physical acts such as bowing and kissing to render honor and recognition to the person depicted through the image. Using the Council’s own definition:

“The honor (τιμητική προσκύνησις) paid to the image passes to the prototype, and whoever venerates the image venerates in it the person depicted.”

Both the Eastern Orthodox and Catholic churches fully embrace this statement and are very careful to state that veneration is not worship. Both churches categorically forbid the worshiping of anything other than God Himself. In both camps the veneration of icons is seen as more than symbolic and less than sacramental.

Catholic believers are permitted to practice icon veneration but are not compelled by their leadership. Orthodox faithful however, are taught to do so regularly and there is a low tolerance within this denomination for the absence of iconography. Official decrees such as the 9th century Synodikon of Orthodoxy re-iterate that honoring saints through icon veneration is part of a Christian’s devotional life.

Orthodox Church are visually ordered around icons and individuals are encouraged to have them at home. Icon veneration is — according to Orthodoxy — designed to help one enter into a personal experience of the Divine and the family of past believers. As though encountering them in real life. The belief is that it renders the focus of one’s prayers more concrete and less abstract. An Orthodox believer will typically face the icon, make the sign of cross, bow, kiss the hands and/or garment of the icon and back away respectfully. Prayers are usually done before or after this act.

By disciplining the body to express respect to God and His saints the Orthodox believer aims to focus his/her soul on the reality of the after life and their own mortality. Rituals helping to focus on God and one’s salvation helps the individual to attain or maintain a state of grace. Being in a state of grace is crucial because should they die, they must be in such a state in order to be saved.

Participation is not optional for Orthodox believers. The Second Council of Nicaea forbade the public refusal to venerate icons. In fact, in the Byzantine Empire from 726 to 843 two major conflicts arose among Orthodox believers. Some were for and others against icon veneration. These deadly conflicts occurred before, during and after the Second Nicene council. On March 11, 843 AD Empress Theodora deposed patriarch John VII Grammatikos and returned icons to the Hagia Sophia, marking an end to the “iconoclastic wars.”

You cannot be officially be fully in communion with any Orthodox branch if you do not participate publicly in icon veneration. Although it is not explicitly deemed an act of worship, it is a core part of the life of an Orthodox believer. A willful rejection of icon veneration, after it has been defined by the church at a universal council, constitutes a rejection of Orthodox faith and communion, which was once seen as a serious detriment to salvation.

Are We Not Forbidden to Make Images?

Many Reformed Christians have a knee-jerk reaction against the mandatory use of images during religious service. The Second Commandment ominously states:

“You shall not make for yourself a carved image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. You shall not bow down to them or serve them, for I the Lord your God am a jealous God,”

– Exodus 20:4-5

This commandment is explicitly against idolatry. Men bow to their superiors and call them Lord throughout the bible. God had Moses raise up a bronze serpent and whomever looked upon the serpent would be healed from their poisoning (Numbers 21:4-9). God ordained His tabernacle, Ark and priests to be fitted with images of trees, fruit and Cherubim. Each tribe in the desert was asked — by God — to designate a standard for themselves (Num. 2:2). Imagery present in places of worship is not automatically idolatry.

Note that in none of these above biblical examples are the images to be directly focused on during religious rituals. They were merely present during sacred duties and worship or public assembly.

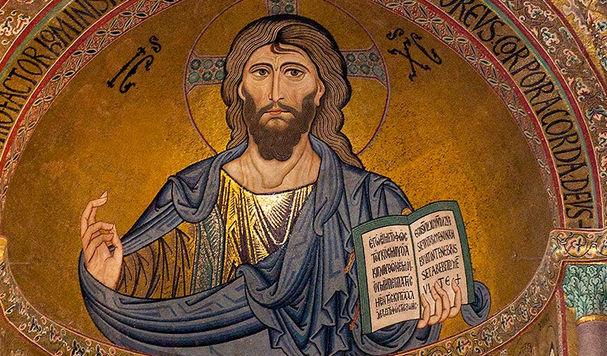

I consider the Shroud of Turin the world’s first photograph and it captured the moment of Christ’s bodily Resurrection in image form. Not only did men and women see Christ during the Incarnation, but the whole word was left with an image that has been treasured by the Church ever since. And as early as the mid third century Christians began depicting Christ for commemoration and education purposes.

Images by themselves, even when involved in church service are not necessarily being worshiped.

Tension Between Reverence and Worship

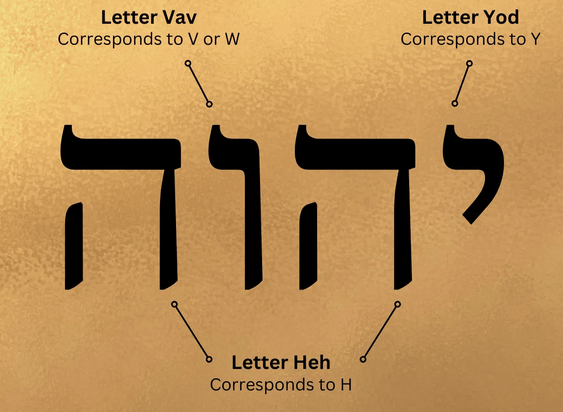

In Revelation, John falls at the feet of an angel to “worship.” Immediately the angel pulls him up exclaiming “you must not do that!” The verb proskyneō (προσκυνέω) is used in the Greek, which we render as ‘worship’ in Rev. 22:8:

1. to kiss the hand to (towards) one, in token of reverence

2. to fall upon the knees and touch the ground with the forehead as an expression of profound reverence

3. by kneeling or prostration to do homage (to one) or make obeisance, whether in order to express respect or to make supplication

Throughout the New Testament the verb proskyneō is used to describe people’s rightful reaction to God or to Christ. This is deemed proper worship. When it is used to describe unbelievers bowing to the anti-christ or fallen spirits, it is condemned. One time only is it used to describe civic respect: the parable of the debtor desperately kneeling before a king. Although the king does represent God in this parable, the act is not translated as “worship” but as “kneeling before.” Only twice do we see the ‘worship’ version of proskyneō applied to someone reacting to a ‘good guy’ that isn’t Christ or God the Father: when John prostrates in front of the angel (above example) and when the Roman centurion Cornelius proskyneō‘s to Peter in Acts 10:25. In both cases it is condemned. Peter quickly lifts Cornelius up and states “I too am a man.”

If Peter the apostle did not accept proskyneō and neither did angels, what makes us think it is now okay to do so through the icons? Remember that I accept that the intent of icon veneration is to the person themselves and not the physical image. I am allowing the Catholics and Orthodox to bypass the issue of idolatry in this sense. The definition of proskyneō includes the showing of reverence through kissing hands, kneeling and bowing, all of which are acceptable to do during icon veneration in the Orthodox and Catholic churches but not acceptable by Peter or the angel when done to them in person.

This creates a tension for me but not an absolute brick wall. Remember that in 1 King 1:23 Nathan the prophet commits proskyneō before King David and the beggar in Matt. 18 does so before his own king. Neither are condemned. The Catholic/Orthodox argument that not all proskyneō is worship has merit and precedence. Proskyneō is not automatically worship and idolatry. Five times in the New Testament the word latreia (λατρεία) appears, signifying sacred worship. Unlike proskyneō this word absolutely cannot be divorced from its sacramental and spiritual designation and is never used for anyone or anything but God Himself.

“This true and absolute worship,” say Catholics and Orthodox “is what we forbid, even to icons.”

Fair enough. Scripture does permits a category of bodily reverence, while simultaneously reserving true worship—λατρεία—for God alone.

What Do the Church Fathers Say?

The Second Council of Nicaea claims that icon veneration was handed to us by the apostles and their students. Early Church Fathers would approve, is the claim.

Is this true?

`The oldest known image of Christ is a fresco in Syria dating to about the 240s AD. Around the same time period we date a Roman catacomb image of Jesus. I could find no reputable Catholic or Orthodox scholarship that claimed these were used as anything but commemorative, symbolic or didactic. Consensus is that these were not veneration tools.

Written sources indicate that in the final decades of the fourth century, biblical imagery and painted martyr scenes became increasingly prominent in Christian life, coinciding with the rise of martyr shrines and the public cult of relics. During this period, images were valued for commemoration, instruction, and emotional engagement. However, the ritual or devotional use of images—such as kissing, bowing, or offering lamps or incense—remains historically uncertain and sparsely attested until the late sixth century, when both textual and material evidence becomes clear and widespread.

At Mars Hill in Athens we see Paul categorically renouncing Greek idols saying:

“we ought not to think that the divine being is like gold or silver or stone, an image formed by the art and imagination of man.”

– Acts 17:29

This seems to set the tone for the next few hundred years of Patristic tradition.

Church Fathers for the first 500 years of the faith opposed pagan idolatry, yet they did so with a broadly prohibitive posture toward religious imagery itself—making it historically implausible that they anticipated or endorsed the later emergence of a distinctly Christian system of image veneration.

For the first century of the Church there is no mention of imagery by the fathers. In the 150s and 160s AD, Justin Martyr makes mention of the pagan use of idols. He also makes clear anti-imagery statements:

“For it is irrational to venerate things that are handmade, lifeless, and without perception.”

- Dialogue with Trypho, Ch. 55 ~155 AD

Writing to Emperor Marcus Aurelius and his son Commodus in the 170s AD, Athenagoras pleads on behalf of Christians who are being persecuted by Rome. Chapters 15 to 17 include defenses against accusations of idolatry by pointing out that Christians do not use imagery in their religious practices:

“But since we say that God is eternal, impassible, indivisible, and uncreated, and that He cannot be contained by any place, nor encompassed by any form, what need is there of images?

For God is mind and reason, not matter; He is not seen by the eyes, nor grasped by sense.”

- Petition on Behalf of Christians, chapter 15

And:

But we do not apprehend God by sight, nor do we approach Him through sense perception,

but by the mind and by reason.

For He is not like created things, nor is He known through visible forms, but through the understanding and contemplation of the soul.”

- Petition on Behalf of Christians, chapter 17

In an early church that practiced icon veneration, a statement like this would never be made. Instead we would see a defense of icons, differentiating them from pagan imagery. We see only the declaration that no images, whatsoever, are part of Christian religious or devotional life.

Irenaeus of Lyons criticizes the Marcosian gnostic sect’s images of Christ and their use of these in religious ceremonies. He treats this as a mark of heretical paganism:

“They also possess certain images, some painted and others formed from various materials, saying that an image of Christ was made by Pilate at the time when Jesus lived among men.

And they crown them, set them up, and adore them, and do all the other things which the pagans also do.”

- Against Heresies, Book 1 Ch. 25 line 6 ~180s AD

The first explicit Christian-era reference to image veneration appears not in the Church, but among condemned Gnostic sects who practiced pagan-style devotion under the name of Christ.

Clement of Alexandria and Tertullian only speak specifically against pagan idolatry. Then Origen comes onto the scene in his polemic against Platonist pagan philosopher Celsus in 248 AD. One of the charges leveled at Christians was that they had no temples, altars or images in their worship. Origen does not deny the charge. Instead, he embraces it—arguing that Christian worship is deliberately non-material, non-localized, and not mediated through physical representations:

“The Greeks think it pious to worship statues, but we do not think it right even to make images of divine things.

We believe that God is better honored by righteous conduct and virtuous living than by lifeless representations. The true image of God is found in the rational soul that imitates Him through holiness and virtue.”

- Against Celsus, VII.62

This is not distinguishing Christian icon veneration from pagan idolatry but a flat denial that Christians engage in anything resembling this practice:

“Christians are said to have no temples, no altars, and no images…

…For they do not suppose that God ought to be honored through sensible things, but through the purity of the mind and the contemplation of reason (the Logos).”

- Against Celsum, VII.64

As Christ told the Samaritan woman that God desired to be worshiped in “spirit and in truth” Origen tells Celsus that Christians access God without physical mediation. As a standard.

In the 320s AD the half sister of Emperor Constantine — a wealthy and powerful Christian convert and patron named Constantina — requested a portrait of Christ from bishop Eusebius of Caesarea Maritima. Writing back, he explained why he believed it was inappropriate to provide any image of Christ, whether in His Glorified state or his humble incarnation:

“if you mean that form which He bore before He took the form of a servant, even Moses could not look upon it, nor could any man behold it and live.

But if you mean the form which He assumed when, for our salvation, He clothed Himself in a mortal body, how could this be depicted…

…How, then, could anyone depict in an image the form of Christ…

…such practices belong to the error of the pagans…

…we, who have been taught to worship God in spirit and in truth… …not… … in material and perishable forms…

…it seems to me that such a request is not appropriate, nor in keeping with the true understanding of the Christian faith. For it is not by means of images made with hands that we are taught to know our Savior, but by the word of God and by the contemplation of His divine nature through faith.”

- Letter to Constantina PG 20, columns 1545–1548

I think the bishop went farther than Scripture warrants and do not feel images of Christ are inappropriate in commemorative settings. Yet, it is safe to say the bishop of Caesarea Maritima would not have been amenable to the veneration of icons.

In 394 AD, Epiphanus, bishop of Salamis wrote to the bishop of Jerusalem to tell of an anecdote:

“When I came to a village called Anablatha,

and saw there a curtain hanging on the doors of the church,

which bore an image, as it were, of Christ or of some saint —

I do not clearly remember which —

I tore it down, and advised the keepers of the place

to use it to wrap a poor dead man.

For I said that it is contrary to the authority of the Scriptures

for an image of a man to hang in the church of Christ.”

- Jerome, Epiphanius’ letter to John 51.9 PG 43.385-389

This passage is preserved in a 394 AD letter from Jerome, a priest at Antioch, which he wrote to Roman senator Pammachius approving of the bishop’s zealous action:

“I approve of his zeal and his faith, for he acted in accordance with the Scriptures.”

- Letter to Pammachius 51.9

Basil the Great is quoted in the Second Council at Nicaea for this statement made in 375 AD:

The honor paid to the image passes to the prototype,

and whoever venerates the image,

venerates in it the reality of the one depicted.

- On the Holy Spirit ch. 18.45

However, Basil here is speaking strictly of Christ, the Son of God as the image and prototype of God the Father. He was explaining that devotion to Christ passes to the Father and does not therefore prioritize the Son over the Father. He said nothing of physical imagery.

8th Century AD – Clashes Over Icons

From the time of the apostles until the end of the 7th century the church fathers are either silent or they speak explicitly against the religious use of imagery. It is not until John of Damascus in the 720s AD that we get a full throated approval of icon veneration:

“I venerate the icon of Christ,

not as God, but as the image of God who became incarnate.”

- First Treatise 16

“Worship (latreia) belongs to the divine nature alone,

but veneration and honor are given to the saints and to icons.”

- First Treatise 21

“For the honor paid to the image passes to the prototype.”

- First Treatise 21

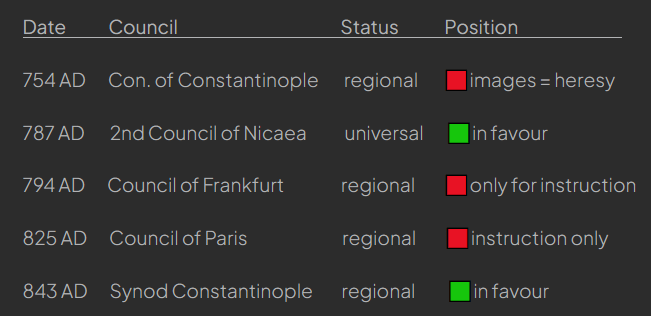

John did not invent icon veneration. We have evidence that the laity began practicing this in rudimentary form as early as the late 6th century AD. After a hundred or so year of this practice growing in the church it became a matter for the leadership to deal with. A series of regional councils were launched as well as a universal one. The results were as follows:

The late 9th century saw the Eastern Church squash the internal fighting — theological and literal — and usher in the age in which icon veneration became an uncontroversial practice across Christendom until the Reformation in the 15th century.

IN CONCLUSION

It is historically undeniable the icon veneration was unknown to the Church for approximately 4 centuries after Christ’s Ascension. As it grew into a common practice it ushered in over a century of controversy. Leading to bloody conflicts within the Easter Church that lasted 117 years.

When looking at the traditional patristic stances on things like baptism and the Eucharist, we see extremely early and unanimous approval that is unbroken even by the Reformation schism of the Western Church. It is hard to deny the Holy Spirit’s role in such instances.

That is not the case for practices such as the invocation of the saints and the veneration of icons. Instead we see early absence, late introduction and consequently severe controversy.

The decree in the Second Council of Nicaea (787 AD) contradicted the local councils before and after it. Further, it mandated — not suggested — imagery be present in all churches by order of the bishops. Both for symbolic and veneration purposes. The last line in the decree was severe:

Therefore, those who dare to think or teach otherwise, or to reject the ecclesiastical traditions, or to destroy the sacred images, or to call them idols, or to introduce any innovation, we anathematize.

In the eighth century the technical term “anathema” was the strongest canonical penatly the Church could impose. It meant to be found outside the Church’s sacramental and communal life for obstinate doctrinal error. This was as close to pronouncing someone’s damnation as a leadership body could go. The reason this undermines my confidence in this last universal council is that it would likely have ex-communicated many earlier fathers such as Justin Martyr, Irenaeus and Origen. Which seems ludicrous to me.

I do not believe the men and women in Orthodox or Catholic churches are automatically committing idolatry for taking part in veneration of icons. Most — I would dare say almost all — are merely looking to honour God by being faithful to what they believe is correct devotional practice. It is my view that all branches in Christendom contain practical errors. In some Reformed branches there are mistaken views on the Eucharist and baptism. Does the God of grace condemn people whose flaws flow downstream from their leadership? No. When the intent of the heart is to draw close to God, errors of innocence or ignorance are not paramount.

That said, I remain convinced that the veneration of icons is a later doctrinal accretion — neither biblical, apostolic, nor early patristic in origin. I see it as a consequence of Greco-Roman religious culture gradually seeping into the life of the Church. All theological error carries consequences. Iconography can introduce unnecessary distance between the believer and Christ. It can create a bureaucratic layer of mediation that was never intended. It can foster a transactional confidence that subtly displaces heartfelt repentance and personal communion with God. Not always and not mortally so.

In my view, the Second Council of Nicaea’s dogmatic imposition of such a questionable practice undermines the council’s credibility. I do not see how it successfully justifies the practice either historically or biblically. Yet this conclusion carries no weight whatsoever in how I regard Catholic and Orthodox believers. They remain, unequivocally, my born-again brothers and sisters in Christ.

I simply will not be joining them in this practice.